Anyone who walks around Norfolk, visit stores or even your local library, you can see that the tattoo culture is thriving, especially among women. In fact in 2012, was the first year in which more women were tattooed then men. Once Norfolk was the reputed tattoo capital of the nation, and to some the World. In the 1930s and ’40s, Norfolk’s East Main Street was world famous for its tattoo parlors, taverns and burlesque palaces. Sailors from around the world use to come to Norfolk and crowd East Main Street to get a tattoo from world famous August “Cap” Coleman one of the God Fathers of tattooing.

Tattoos became especially widespread during World War II, when the Navy’s ranks reached 3 million. Tattoos and sailors became linked, but often the sailors got drunk to work up their courage to get a tattoo, so the ports where the tattoo parlors were located came to be seen as mighty seedy places. In Norfolk in 1945, there were about a dozen parlors to choose from, and word began to spread that if you needed an eagle or “USN” on your arm, Norfolk was the place to get it. And there were many famous Tattoo artists that did their practice here, but did you know that there was a famous lady tattooist who became famous here and is also buried in Norfolk’s Forest lawn Cemetery?

Tattoos became especially widespread during World War II, when the Navy’s ranks reached 3 million. Tattoos and sailors became linked, but often the sailors got drunk to work up their courage to get a tattoo, so the ports where the tattoo parlors were located came to be seen as mighty seedy places. In Norfolk in 1945, there were about a dozen parlors to choose from, and word began to spread that if you needed an eagle or “USN” on your arm, Norfolk was the place to get it. And there were many famous Tattoo artists that did their practice here, but did you know that there was a famous lady tattooist who became famous here and is also buried in Norfolk’s Forest lawn Cemetery?

Here name was Lenora Platt Blair, but you will find for tattooing and carnival work she went by her maiden name. She was born in Pittsburg, PA in 1883. I was approached by my friend David Stevens last week if I ever heard of her. Which I have to admit that I did not, and that is a shame really. She led an interesting life, but not much is known about her life, expect she was a pioneer in tattooing. Not much is known about her early life, expect that around 1912 she got her first tattoo and also began to tattoo people as well. What we do know is that early in her life she traveled with carnivals all over the country and sometimes in dime museums. Life in Carnivals was rough and the pay was next to nothing.

went by her maiden name. She was born in Pittsburg, PA in 1883. I was approached by my friend David Stevens last week if I ever heard of her. Which I have to admit that I did not, and that is a shame really. She led an interesting life, but not much is known about her life, expect she was a pioneer in tattooing. Not much is known about her early life, expect that around 1912 she got her first tattoo and also began to tattoo people as well. What we do know is that early in her life she traveled with carnivals all over the country and sometimes in dime museums. Life in Carnivals was rough and the pay was next to nothing.

During World War I she was a part of Sheesley Traveling  Carnival who decided to set up here in Norfolk to ride out the cold winter months. This was the perfect opportunity for Lenora, Norfolk was in process of reinventing itself as the Tattoo Capital of North America. She opened a shop in Newport News on Washington Avenue. The name of the shop is unknown for now, she should be in Newport News City Directory, but that is for an article in the future. Since she was woman and next to the naval base in Newport News men flocked her store for tattoos, and many just came to see a woman tattoo which was for the time very taboo.

Carnival who decided to set up here in Norfolk to ride out the cold winter months. This was the perfect opportunity for Lenora, Norfolk was in process of reinventing itself as the Tattoo Capital of North America. She opened a shop in Newport News on Washington Avenue. The name of the shop is unknown for now, she should be in Newport News City Directory, but that is for an article in the future. Since she was woman and next to the naval base in Newport News men flocked her store for tattoos, and many just came to see a woman tattoo which was for the time very taboo.

Some blogs have reported that in January 1918, a Sgt. Hill told the police that Lenora was a spy for the Germans. Having no evidence the charges against her were dismissed. Today, I have found no evidence that this even took place. I will have to look through all the Newport News Newspapers in January 1918 to see if this is even true, I will keep everyone informed if I find anything.

a spy for the Germans. Having no evidence the charges against her were dismissed. Today, I have found no evidence that this even took place. I will have to look through all the Newport News Newspapers in January 1918 to see if this is even true, I will keep everyone informed if I find anything.

For some reason after World War I came to an end she decided to travel with carnivals in the summer and during the winter months tattooing in Hampton Roads. Carnivals were probably the best way for a woman at the time to advertise her particular skills. Eventually she opened a shop on East Main Street with some of the best talents in the country. In a 1919 Billboard Ad, Lenora was employing two other ladies at her store, because business was booming. She was one of the first lady tattooist in the world. A year later her competitors were advertising for women artists to join them so they could compete against her.

She was married five times, none of her husbands were in the tattooing world, and none of her marriages lasted very long. No one knows for certain why they did not work out. No doubt long hours at the shop and sometimes traveling with carnivals had played a big part in it. She had no children and retired in the 1930’s due to an illness. She died on October 28, 1960 at the age of 77. She is buried at Forest lawn at Northeast Center II, Block T, Space 5 in an unmarked grave. Having no children or a spouse and not being from Norfolk, there was no one here to place a stone on her plot. She was a remarkable woman who had to face discrimination and sexism in a field that was heavily dominated by men. Not only did she excel at it, she did better than her male competition did here in Norfolk. I been told that there is a movement in the Norfolk tattoo community to get a stone placed on her plot. She was a pioneer and she deserves to be remembered.

She was married five times, none of her husbands were in the tattooing world, and none of her marriages lasted very long. No one knows for certain why they did not work out. No doubt long hours at the shop and sometimes traveling with carnivals had played a big part in it. She had no children and retired in the 1930’s due to an illness. She died on October 28, 1960 at the age of 77. She is buried at Forest lawn at Northeast Center II, Block T, Space 5 in an unmarked grave. Having no children or a spouse and not being from Norfolk, there was no one here to place a stone on her plot. She was a remarkable woman who had to face discrimination and sexism in a field that was heavily dominated by men. Not only did she excel at it, she did better than her male competition did here in Norfolk. I been told that there is a movement in the Norfolk tattoo community to get a stone placed on her plot. She was a pioneer and she deserves to be remembered.

NWF wanted him to be more active in urging passage of the amendment. President Wilson left Washington in December 1918 to attend the international peace conference in Versailles. In January 1919, the National Woman’s Party devised a new tactic to pressure for the adoption of a suffrage amendment to the Constitution. Members would gather with copies of the president’s speeches on issues relating to democracy and burn them in urns outside public buildings, including the White House. With a banner implying that the resident was a hypocrite, women outside the White House burned a speech Wilson had given on his grand tour of Europe. These “Watch Fires of Freedom” resulted in more arrests and often provoked counter demonstrations.

NWF wanted him to be more active in urging passage of the amendment. President Wilson left Washington in December 1918 to attend the international peace conference in Versailles. In January 1919, the National Woman’s Party devised a new tactic to pressure for the adoption of a suffrage amendment to the Constitution. Members would gather with copies of the president’s speeches on issues relating to democracy and burn them in urns outside public buildings, including the White House. With a banner implying that the resident was a hypocrite, women outside the White House burned a speech Wilson had given on his grand tour of Europe. These “Watch Fires of Freedom” resulted in more arrests and often provoked counter demonstrations. almost forgotten to history. Many important women did take part in the protests, but anyone who was minority was pushed out of the lime light. It was a time when segregation was still very popular in the southern states and racism was everywhere especially in Norfolk. Nell was a member of the Norfolk branch of the NWP, who president was the famous Pauline Adams, the two were close friends. In the final Watch Fire of Freedom protest Nell Mercer was arrested and spent five days in prison. She did not regret anything she had done, she 100% believed in the cause the women deserved the right to vote.

almost forgotten to history. Many important women did take part in the protests, but anyone who was minority was pushed out of the lime light. It was a time when segregation was still very popular in the southern states and racism was everywhere especially in Norfolk. Nell was a member of the Norfolk branch of the NWP, who president was the famous Pauline Adams, the two were close friends. In the final Watch Fire of Freedom protest Nell Mercer was arrested and spent five days in prison. She did not regret anything she had done, she 100% believed in the cause the women deserved the right to vote.

members of the ESL sought to educate Virginia’s citizens and legislators and to win their support for woman suffrage. Beginning in 1914, the group published its own monthly newspaper, the Virginia Suffrage News, under managing editor Alice Overby Taylor and editor in chief Mary Pollard Clarke. Valentine persuaded a group of Richmond businessmen to form the Men’s Equal Suffrage League of Virginia, and Johnston visited women’s colleges to rally faculty and students to the cause. Local leagues soon sprang up across the state.

members of the ESL sought to educate Virginia’s citizens and legislators and to win their support for woman suffrage. Beginning in 1914, the group published its own monthly newspaper, the Virginia Suffrage News, under managing editor Alice Overby Taylor and editor in chief Mary Pollard Clarke. Valentine persuaded a group of Richmond businessmen to form the Men’s Equal Suffrage League of Virginia, and Johnston visited women’s colleges to rally faculty and students to the cause. Local leagues soon sprang up across the state. between Adams and Townsend was apparent during Adam’s last election to the presidency of the Norfolk league, in December 1912 in the Green Room of the Lynnhaven Hotel. The meeting was contentious, with three candidates – Pauline Adams and the two League vice presidents, Lilla W. Bain and Florence A. Tait – vying for the presidency. Adams announced before the vote that no proxies would be allowed, which prompted “a hot discussion,” in the measured words of league Secretary Sarah Sandbridge. The members voted on the proxy question and upheld Adams’s position, which prompted a number of members to leave. Evelyn Southall motioned to postpone the election and adjourn, sparking “another warm discussion.” Some argued that absent league members who had entrusted their proxies to others were unfairly losing their chance to vote; other were unfairly losing their chance to vote; other replied that voting by proxy had never been the practice in the local, state, or national suffrage leagues and that the date of the election had been advertised well in advance.

between Adams and Townsend was apparent during Adam’s last election to the presidency of the Norfolk league, in December 1912 in the Green Room of the Lynnhaven Hotel. The meeting was contentious, with three candidates – Pauline Adams and the two League vice presidents, Lilla W. Bain and Florence A. Tait – vying for the presidency. Adams announced before the vote that no proxies would be allowed, which prompted “a hot discussion,” in the measured words of league Secretary Sarah Sandbridge. The members voted on the proxy question and upheld Adams’s position, which prompted a number of members to leave. Evelyn Southall motioned to postpone the election and adjourn, sparking “another warm discussion.” Some argued that absent league members who had entrusted their proxies to others were unfairly losing their chance to vote; other were unfairly losing their chance to vote; other replied that voting by proxy had never been the practice in the local, state, or national suffrage leagues and that the date of the election had been advertised well in advance.

who was Vice President of the League and Evelyn Southall their stories fade into history. But their hard work and determination no doubt helped women get the right to vote six years later. Though not major players in the league they did their part to ensure that voice was heard in their own way. Hopefully by 2020 the 100 year anniversary of the 19th Amendment I will have found more of these two women. Jessie Townsend we talked about earlier today and you can read all about her there. This will be the last entry for Women’s International Day. Stay tuned for more historic women this month.

who was Vice President of the League and Evelyn Southall their stories fade into history. But their hard work and determination no doubt helped women get the right to vote six years later. Though not major players in the league they did their part to ensure that voice was heard in their own way. Hopefully by 2020 the 100 year anniversary of the 19th Amendment I will have found more of these two women. Jessie Townsend we talked about earlier today and you can read all about her there. This will be the last entry for Women’s International Day. Stay tuned for more historic women this month.

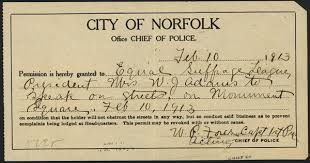

Association president Anna Howard Shaw and Equal Suffrage League of Virginia president Lila Hardaway Meade Valentine. It was the third local league organized in the state and became one of the largest and most active. Elected treasurer in 1911, Townsend marched with more than a hundred Virginians in the 3 March 1913 suffrage parade in Washington, D.C. She attended state conventions regularly during the decade and was a Virginia delegate to the national conventions of the National American Woman Suffrage Association from 1913 to 1917. Townsend also joined the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (later the National Woman’s Party), but withdrew after its 1915 convention.

Association president Anna Howard Shaw and Equal Suffrage League of Virginia president Lila Hardaway Meade Valentine. It was the third local league organized in the state and became one of the largest and most active. Elected treasurer in 1911, Townsend marched with more than a hundred Virginians in the 3 March 1913 suffrage parade in Washington, D.C. She attended state conventions regularly during the decade and was a Virginia delegate to the national conventions of the National American Woman Suffrage Association from 1913 to 1917. Townsend also joined the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (later the National Woman’s Party), but withdrew after its 1915 convention. fairs, to women’s clubs, and to schools and church groups. She later chaired the Norfolk branch’s legislative committee, whose members in 1915–1916 secured signatures on suffrage petitions sent to the General Assembly and contacted local legislators and members of Congress to advocate voting rights for women. After the state league endorsed a federal suffrage amendment in November 1917, Townsend and others circulated petitions and wrote the chairman of the House of Representatives’ Committee on Woman Suffrage to urge passage of the amendment.

fairs, to women’s clubs, and to schools and church groups. She later chaired the Norfolk branch’s legislative committee, whose members in 1915–1916 secured signatures on suffrage petitions sent to the General Assembly and contacted local legislators and members of Congress to advocate voting rights for women. After the state league endorsed a federal suffrage amendment in November 1917, Townsend and others circulated petitions and wrote the chairman of the House of Representatives’ Committee on Woman Suffrage to urge passage of the amendment. constitution and was named director of the Second Congressional District, encompassing the counties of Isle of Wight, Nansemond, Norfolk, Princess Anne, and Southampton and the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth. She presided at the final meeting of the Equal Suffrage League on 9 November 1920 and the founding meeting of the League of Women Voters the following day. When the Norfolk branch of the League of Women Voters was formed, she was elected a director-at-large. She served as its president from 1928 to 1930. At the 1926 state convention in Lynchburg, the members honored Townsend with a silver loving cup.

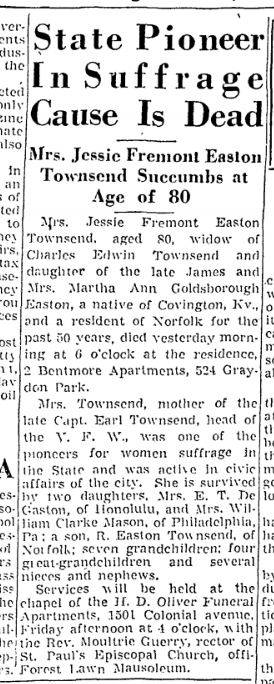

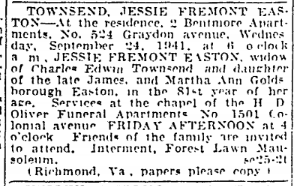

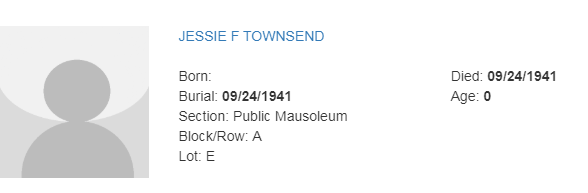

constitution and was named director of the Second Congressional District, encompassing the counties of Isle of Wight, Nansemond, Norfolk, Princess Anne, and Southampton and the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth. She presided at the final meeting of the Equal Suffrage League on 9 November 1920 and the founding meeting of the League of Women Voters the following day. When the Norfolk branch of the League of Women Voters was formed, she was elected a director-at-large. She served as its president from 1928 to 1930. At the 1926 state convention in Lynchburg, the members honored Townsend with a silver loving cup. Townsend’s husband died on 23 June 1930, and her son Charles Earle Townsend died as the result of an automobile accident the following year. Jessie Fremont Easton Townsend suffered from poor health during the final years of her life. She lived with her sole surviving son in Norfolk and died of heart failure at his home on 24 September 1941. She was buried in Norfolk’s Forest Lawn Cemetery’s Mausoleum beside the bodies of her husband and older son. Her obituary in the Norfolk Virginian-Pilot appropriately identified her as a “State Pioneer in Suffrage Cause.”

Townsend’s husband died on 23 June 1930, and her son Charles Earle Townsend died as the result of an automobile accident the following year. Jessie Fremont Easton Townsend suffered from poor health during the final years of her life. She lived with her sole surviving son in Norfolk and died of heart failure at his home on 24 September 1941. She was buried in Norfolk’s Forest Lawn Cemetery’s Mausoleum beside the bodies of her husband and older son. Her obituary in the Norfolk Virginian-Pilot appropriately identified her as a “State Pioneer in Suffrage Cause.”