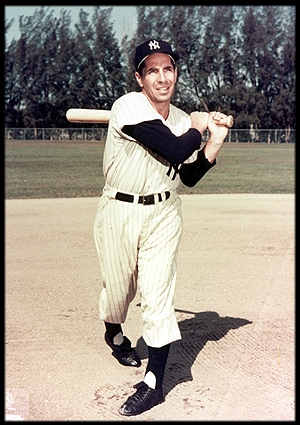

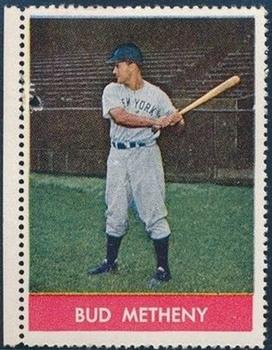

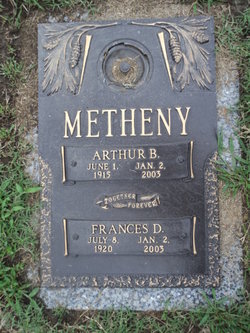

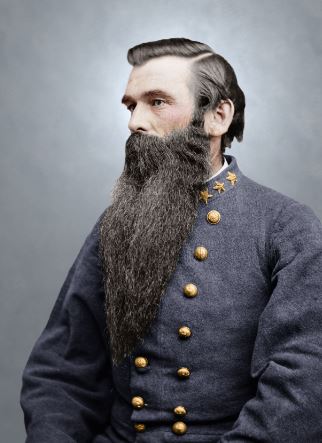

Who was the last Yankee player to wear Babe Ruth’s uniform number 3 before it was  retired by the New York Yankees? It was Arthur Beauregard “Bud” Metheny, a wartime outfielder (1943-46). Metheny was born on June 1, 1915, in St. Louis. He was of Scotch-Irish-English-Indian descent. On his mother’s side his great-grandmother was a full-blooded descendant of Pocahontas. His middle name, Beauregard, was in honor of his grandfather, Pierre G.T. Beauregard, who was named after the Confederate general who fired the first shot on Fort Sumter.

retired by the New York Yankees? It was Arthur Beauregard “Bud” Metheny, a wartime outfielder (1943-46). Metheny was born on June 1, 1915, in St. Louis. He was of Scotch-Irish-English-Indian descent. On his mother’s side his great-grandmother was a full-blooded descendant of Pocahontas. His middle name, Beauregard, was in honor of his grandfather, Pierre G.T. Beauregard, who was named after the Confederate general who fired the first shot on Fort Sumter.

Metheny’s father was an electrician in St. Louis, where at the age of 12 Metheny played American Legion baseball. The family moved to Virginia, where Metheny attended Calverton High School. He was a pitcher until he developed elbow trouble. While playing semipro ball in Culpeper, Virginia, and in Vermont, he was scouted by Gene McCann. In June 1938, while Metheny was at the College of William & Mary, McCann signed him to a Yankees contract. He played in 89 games for the Norfolk Tars in 1938, hitting .338 with 21 home runs, the most he would ever hit in a season.

Metheny graduated from William & Mary in 1939.4 He paid his way through college working in the dining hall and by serving as circulation manager for the school newspaper. He found time to join Phi Kappa Tau fraternity and play football.5 After graduation he was certified to teach high-school biology, chemistry, and mathematics. While playing freshman football at William & Mary, Metheny suffered a knee injury that had a long-lasting effect on his ability to run.

In 1939 Metheny played with the Kansas City Blues of the American Association, for whom he hit 10 home runs and batted .315 in 95 games. That season he again hurt his left knee, while sliding, and was out for close to two months. After the season surgeons at Johns Hopkins Hospital removed a piece of cartilage from his knee and scraped a bone growth. Because of inactivity after the procedures, he bulked up to 200 pounds. In 1940 Metheny played for the Newark Bears of the International League, for the 1940 season, where he batted .308 and his 102 RBIs helped the Bears win the pennant and the Junior World Series over Louisville, the American Association champion.

In 1939 Metheny played with the Kansas City Blues of the American Association, for whom he hit 10 home runs and batted .315 in 95 games. That season he again hurt his left knee, while sliding, and was out for close to two months. After the season surgeons at Johns Hopkins Hospital removed a piece of cartilage from his knee and scraped a bone growth. Because of inactivity after the procedures, he bulked up to 200 pounds. In 1940 Metheny played for the Newark Bears of the International League, for the 1940 season, where he batted .308 and his 102 RBIs helped the Bears win the pennant and the Junior World Series over Louisville, the American Association champion.

Metheny’s Married Frances Davis of Norfolk on Valentine’s Day. The two had met at William and Mary. Frances graduated in 1939 and became a teacher and librarian in the Norfolk public school system. During the offseason Metheny stayed in shape working as a fireman on a locomotive crane, picking up 60-ton loads at the naval base in Norfolk. By the end of the 1942 season, after five years in the minors, Metheny was known to be a vigorous left-handed swinger and the only left-handed thrower among the Yankees outfielders.1

In a spring training game in 1943 against the Brooklyn Dodgers, Metheny tripled over the head of Joe Medwick with a shot that was declared the hardest-hit ball of the game.13 He also doubled and walked twice in the game. Even so, an outfield of Metheny, Lindell, and Stormy Weatherly hardly compared with DiMaggio, Keller, and Henrich.

When Metheny made the Yankees roster for the 1943 season he joined Weatherly, who was part Cherokee, as the two Yankees who were part Native American. Metheny made his major-league debut on April 27, 1943, at Fenway Park in Boston. With the Yankees trailing the Red Sox 4-0, he pinch-hit for pitcher Atley Donald in the eighth inning and singled to right field. The next nine times Metheny was sent up to pinch-hit, he failed to get a hit, but he nonetheless collected three RBIs. One was with a bases-loaded walk on May 6 at home against Boston that brought in the tying run. .

In June 1943 Metheny emerged as the club’s starting right fielder. On June 17 at Griffith Stadium, he came in as a defensive replacement in right field for the bottom of the sixth inning. In the top of the ninth, Washington’s Early Wynn walked Metheny with the bases loaded. It proved to be the winning run as the Yankees won, 9-8, with three runs in the ninth. Metheny got his first start in right field the next day in Yankee Stadium against the Red Sox. He went hitless and was now batting .071 with only one hit. On June 20 he started against the Senators, doubled, and was on his way to becoming a mainstay in the lineup.

Stadium, he came in as a defensive replacement in right field for the bottom of the sixth inning. In the top of the ninth, Washington’s Early Wynn walked Metheny with the bases loaded. It proved to be the winning run as the Yankees won, 9-8, with three runs in the ninth. Metheny got his first start in right field the next day in Yankee Stadium against the Red Sox. He went hitless and was now batting .071 with only one hit. On June 20 he started against the Senators, doubled, and was on his way to becoming a mainstay in the lineup.

Starting on July 10, Metheny hit in 10 straight games. He had 18 hits in 40 at-bats, a .450 clip and an on-base percentage of .532 with a .575 slugging percentage. Metheny stole two bases during this 10-game streak, the only two he stole all season. This stretch included a 4-for-4 day on July 21 – the only game the Yankees lost during this period, a 1-0 extra-inning loss to the St. Louis Browns. Though Metheny had four of New York’s nine hits, McCarthy replaced him with a pinch-hitter when faced with a southpaw on the mound. On October 2 in the first game of a doubleheader at home against the Browns, Metheny was a triple shy of the cycle. Batting in his usual second spot in the batting order, he went 3-for-5, knocking in two runs and scoring three in a 5-1 Yankees victory. He finished his very solid rookie season with a .261 average, .333 on-base percentage, and a .397 slugging average. These numbers would turn out to be the best in his career. He hit nine home runs.

The Yankees entered the 1943 World Series with a record of 98-56 and faced the 105-49 St. Louis Cardinals. It gave New York an opportunity to avenge the loss to St. Louis in the five-game 1942 Series. This year proved to be different. In the Series McCarthy alternated  between Stainback and Metheny in right field. Metheny became the goat of the second game, the only Yankees loss. In the top of the fourth inning, trailing 2-0, with one out and Whitey Kurowski on first, Ray Sanders lifted a high fly ball to deep right. The ball glanced off the tip of Metheny’s glove into the stands for a home run. It was believed that Tommy Henrich could have made that catch as he so often reached over the low right field wall in Yankee Stadium to snatch balls out of the stands.15 It put the Cards up 4-0 and they held on to take the game, 4-3. Batting second, Metheny went 0-for-3, reaching base one time on catcher interference. He did not appear again until Game Five, when he started again in right field. He went 1-for-5, with two strikeouts. He was replaced defensively in the bottom of the ninth by Johnny Lindell. The Yankees won the game, 2-0, behind the 10-hit pitching of Spud Chandler, and became the 1943 World Series champion.

between Stainback and Metheny in right field. Metheny became the goat of the second game, the only Yankees loss. In the top of the fourth inning, trailing 2-0, with one out and Whitey Kurowski on first, Ray Sanders lifted a high fly ball to deep right. The ball glanced off the tip of Metheny’s glove into the stands for a home run. It was believed that Tommy Henrich could have made that catch as he so often reached over the low right field wall in Yankee Stadium to snatch balls out of the stands.15 It put the Cards up 4-0 and they held on to take the game, 4-3. Batting second, Metheny went 0-for-3, reaching base one time on catcher interference. He did not appear again until Game Five, when he started again in right field. He went 1-for-5, with two strikeouts. He was replaced defensively in the bottom of the ninth by Johnny Lindell. The Yankees won the game, 2-0, behind the 10-hit pitching of Spud Chandler, and became the 1943 World Series champion.

Metheny got off to a slow start in 1944. On Opening Day he found himself in the lineup as the Yankees beat Boston, 3-0. He went hitless and was 1-for-22 going into the April 26 game against the Philadelphia Athletics, although he continued to hit in the number two spot (He batted second in more than 90 percent of his starts in ’44). He went 2-for-4 that day and knocked in his first run of the season. Four days later, in the second game of a doubleheader at Griffith Stadium, he went 3-for-4 to bring his average to .176 and helped rookie Joe Page win his first career start as the Yankees won, 3-2. This also was the first day of a 22-day period during which Metheny saw his average rise to .292 as he went 28-for-76 with 4 home runs and 14 RBIs. The Yanks won 13 of 19 games and moved from second to first place.

On June 12 the Yankees dropped their sixth straight game, 4-3 in 11 innings. The loss dropped the team into fifth place, only one game from the bottom and three games from first in a very crowded AL race. It was New York’s longest losing streak in four years and the first time they had fallen below .500 since April 29. Twice during the game in Washington, the Yankees charged out of the dugout, but not a blow was believed to have been landed. In the eighth inning, with Metheny on first, Ed Levy grounded to Senators second baseman George Myatt. Myatt tried to tag Metheny and throw on to first to complete the double play. Metheny ducked the tag and back-pedaled. Myatt had to chase Metheny to apply the tag. In the process Metheny kicked dirt on or near Myatt as he got up and the two squared off and tossed a couple of punches with no damage done. Both Myatt and Metheny were ejected. As they made their exit down the stairs adjoining the Senators’ dugout, another scuffle broke out and the two teams piled down together. Eyewitnesses said that the two just gripped each other, but did not engage in any fisticuffs.1 The Yankees pulled ahead in the 10th inning, 3-1, only to see Joe Page blow the lead with two out. The Senators then won in the bottom of the 11th with Atley Donald taking the loss.

On June 12 the Yankees dropped their sixth straight game, 4-3 in 11 innings. The loss dropped the team into fifth place, only one game from the bottom and three games from first in a very crowded AL race. It was New York’s longest losing streak in four years and the first time they had fallen below .500 since April 29. Twice during the game in Washington, the Yankees charged out of the dugout, but not a blow was believed to have been landed. In the eighth inning, with Metheny on first, Ed Levy grounded to Senators second baseman George Myatt. Myatt tried to tag Metheny and throw on to first to complete the double play. Metheny ducked the tag and back-pedaled. Myatt had to chase Metheny to apply the tag. In the process Metheny kicked dirt on or near Myatt as he got up and the two squared off and tossed a couple of punches with no damage done. Both Myatt and Metheny were ejected. As they made their exit down the stairs adjoining the Senators’ dugout, another scuffle broke out and the two teams piled down together. Eyewitnesses said that the two just gripped each other, but did not engage in any fisticuffs.1 The Yankees pulled ahead in the 10th inning, 3-1, only to see Joe Page blow the lead with two out. The Senators then won in the bottom of the 11th with Atley Donald taking the loss.

Metheny was hit with a $50 fine by American League President Will Harridge for his battle with Myatt. He made a personal appeal that he was not at fault and was persuasive enough to have the fine rescinded. Metheny got into another battle in the sixth inning of the July 24 game against the White Sox in Chicago. He and White Sox catcher Tom Turner came close to blows. It was related to an incident in the fourth when Metheny got to first base because Turner tipped his bat.1

Despite the fact that Metheny hit 14 home runs in 1944 while playing in 137 games, he went home after the season with the impression that his .239 batting average had lost the pennant for the Yankees, who finished behind the St. Louis Browns and Detroit. He had plenty of company to take their share of the blame, but Metheny declared himself the number-one goat. On the morning of September 16, the Yankees were in first place. When the season was over on October 1, the Yankees were in third place, six games behind the league champion Browns. It was during this 16-day season-ending stretch that Metheny batted only .158. He knocked in only one run and had only 9 hits in 57 at-bats. The Yanks had a record of 7-7 in the 14 games that Metheny played during the stretch run. What made it even more painful was that the Browns swept the Yankees in the final four games of the season. It is no wonder that Metheny volunteered to wear the goat horns.

Metheny’s 1944 home-run total of 14 was 10th in the AL, a year that saw teammate Nick Etten lead the league with only 22. Adding to Metheny’s feelings of remorse about the season were the 11 errors he made to lead all AL outfielders.

Before the 1945 season McCarthy said that “this could be the best outfield in the AL, maybe even tops in the majors.” Metheny, Lindell, and Hershel Martin were thought to be the primary outfielders with Stainback, Russ Derry, and veteran Paul Waner, at age 42, as backups. The Opening Day starting lineup did not include Metheny, though he did pinch-hit and deliver a sacrifice bunt that advanced a runner who scored in the Yankees’ 8-4 win over the Red Sox. Another slow start saw Metheny hitting an anemic .150 after 26 games. Adding to Metheny’s concern about his role on the Yankees was that by the end of April Derry had hit four home runs, two of them grand slams. (Derry finished the season with 13 home runs in 78 games.)

On May 24 against the White Sox at Yankee Stadium, Metheny went 3-for-4, driving in three runs. He continued to bat in the number-two spot in most of the games he started. He finished the season with a .248 average and 8 home runs in 133 games (more than any other Yankees outfielder). His .983 fielding percentage led all American right fielders. His season highlight took place on June 24 in the first game of a doubleheader in New York. He knocked in six runs on two homers and a double as the Yankees beat the Athletics, 13-5.

In 1946, with the return of DiMaggio, Keller, and Henrich, Metheny had three hitless pinch-hit appearances. His final at-bat for the Yankees came on May 9, after which he was sent down to Kansas City. He finished his major-league career having played 331 games in right field and 11 in left with a .247 average, an on-base percentage of .323, and 31 home runs

After Kansas City Metheny played for Birmingham, Newark, and, in 1948, the Baxley Red Sox, where he was the player-manager of the Class D Georgia State League team. He moved on to the Portsmouth Cubs of the Piedmont League in 1949, and ended his career in 1950 with the Piedmont League’s Newport News Dodgers as player-manager.

Metheny began teaching and coaching at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia, in 1947. He earned a master’s degree in education at William & Mary in 1952. Metheny had a 32-year teaching and coaching career at Old Dominion, compiling a 423-363-6 record as the baseball coach, and was the director of athletics from 1963 to 1970.20 He was named by the NCAA as the Eastern Regional Coach of the Year in 1963 and 1964, and the National Coach of the Year in 1964.21 In 1965 Metheny was named Small College Baseball Coach of the Year. Under Metheny Old Dominion won eight state titles as well as NCAA Eastern Regional crowns in 1963 and 1964.22 He also was the basketball coach from 1948 to 1965, compiling a record of 198-163 with 16 winning seasons. In 1983 Metheny was inducted into the College Baseball Coaches Hall of Fame.23 Still later he was inducted into the Hampton Roads Sports Hall of Fame, the Virginia Sports Hall of Fame, the American Association of College Baseball Coaches Hall of Fame, the William & Mary Hall of Fame, and the Old Dominion University Hall of Fame. On April 25, 1984, Old Dominion named its baseball stadium for Metheny.24

in 1947. He earned a master’s degree in education at William & Mary in 1952. Metheny had a 32-year teaching and coaching career at Old Dominion, compiling a 423-363-6 record as the baseball coach, and was the director of athletics from 1963 to 1970.20 He was named by the NCAA as the Eastern Regional Coach of the Year in 1963 and 1964, and the National Coach of the Year in 1964.21 In 1965 Metheny was named Small College Baseball Coach of the Year. Under Metheny Old Dominion won eight state titles as well as NCAA Eastern Regional crowns in 1963 and 1964.22 He also was the basketball coach from 1948 to 1965, compiling a record of 198-163 with 16 winning seasons. In 1983 Metheny was inducted into the College Baseball Coaches Hall of Fame.23 Still later he was inducted into the Hampton Roads Sports Hall of Fame, the Virginia Sports Hall of Fame, the American Association of College Baseball Coaches Hall of Fame, the William & Mary Hall of Fame, and the Old Dominion University Hall of Fame. On April 25, 1984, Old Dominion named its baseball stadium for Metheny.24

In 1980 Metheny was honored by the Yankees as the first recipient of the “Yankee Family Award.”

Frances Davis Metheny and Arthur Beauregard “Bud” Metheny both died on January 2, 2003, in Virginia Beach and are buried at Colonial Grove Memorial Park, Virginia Beach, Virginia. Frances died in the morning and Metheny several hours later. They had two children, Eileen Carlton and John Metheny, and four grandchildren, Laura Carlton, Beau Metheny, Jeremy Metheny, and Sean Carlton.

Portsmouth, Virginia. Virginia’s parents were William Henry Andrews and Lillian Lilnora Parker Andrews. Virginia was the youngest sibling of the three, and was William and Lillian’s only daughter. William was a navy man and later opened up his own tool and dye business, and Lillian was a telephone operator. Virginia spent her childhood in Portsmouth, Virginia. Later she moved to Rochester, New York to live for a little while, and then moved back to Portsmouth while she attended Woodrow Wilson Public High School. Virginia was a smart student, she even skipped third and sixth grade. During her early teens, Virginia was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. Because of all the failed surgeries to attempt to get rid of the rheumatoid arthritis, Virginia developed crippling arthritis. She ended up in a wheelchair or on crutches. At one point in time she even had a full body cast on. Her family says she had lived her life with very little to no neck movement, and suffered through pain daily.

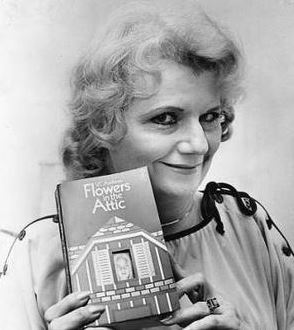

Portsmouth, Virginia. Virginia’s parents were William Henry Andrews and Lillian Lilnora Parker Andrews. Virginia was the youngest sibling of the three, and was William and Lillian’s only daughter. William was a navy man and later opened up his own tool and dye business, and Lillian was a telephone operator. Virginia spent her childhood in Portsmouth, Virginia. Later she moved to Rochester, New York to live for a little while, and then moved back to Portsmouth while she attended Woodrow Wilson Public High School. Virginia was a smart student, she even skipped third and sixth grade. During her early teens, Virginia was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. Because of all the failed surgeries to attempt to get rid of the rheumatoid arthritis, Virginia developed crippling arthritis. She ended up in a wheelchair or on crutches. At one point in time she even had a full body cast on. Her family says she had lived her life with very little to no neck movement, and suffered through pain daily. After graduating at Woodrow Wilson High School, Virginia had more surgeries, attempting to correct the damage to her neck and back. While recuperating, she completed a four year correspondence art course at home. Soon after that she became a successful commercial artist, fashion illustrator and a portrait painter. When Virginia was around 34, her father had a heart attack and died. Virginia and her mother moved from Portsmouth to Manchester, Missouri, to live closer to her older brother. Later they moved again to live closer to her other older brother in Apache Junction, Arizona. Virginia helped support her family with the money she made from her successful career. After she realized that her work lacked her creative satisfaction, she began writing secretly. Her first manuscript was a autobiographical, she destroyed it to keep her private life. At the age of 49, she completed her very first novel, a science-fantasy, “Gods Of Green Mountain.” She never did end up publishing this until April 2004, and even then it was only published in e-book format.

After graduating at Woodrow Wilson High School, Virginia had more surgeries, attempting to correct the damage to her neck and back. While recuperating, she completed a four year correspondence art course at home. Soon after that she became a successful commercial artist, fashion illustrator and a portrait painter. When Virginia was around 34, her father had a heart attack and died. Virginia and her mother moved from Portsmouth to Manchester, Missouri, to live closer to her older brother. Later they moved again to live closer to her other older brother in Apache Junction, Arizona. Virginia helped support her family with the money she made from her successful career. After she realized that her work lacked her creative satisfaction, she began writing secretly. Her first manuscript was a autobiographical, she destroyed it to keep her private life. At the age of 49, she completed her very first novel, a science-fantasy, “Gods Of Green Mountain.” She never did end up publishing this until April 2004, and even then it was only published in e-book format. three Gothic Romances without an agent under a pen name. One of her confession stories, “I Slept With My Uncle On My Wedding Night” was published in an unknown pulp confession magazine. January 13th 1978, Virginia sent a pitch letter to a literary agent with the writers workshop, Anita Diament. Three Days later Anita requested the entire manuscript. Virginia then, submitted her 98 page manuscript, “Flowers In the Attic.” Virginia sold the novel and was paid a $7,500 advance. “Petals On the Wind” was published the very next year and earned Virginia a $35,000 advance. “Petals On the Wind” remained on the bestseller list for 19 weeks, and “Flowers In the Attic” also returned to the list. Both of the novels sold 7 million copies within two years. In 1981 “If There Be Thorns” was released, earning Virginia a $75,000 advance. After this book, Virginia reached number 2 on many best-seller lists within the first two weeks of having the book published.

three Gothic Romances without an agent under a pen name. One of her confession stories, “I Slept With My Uncle On My Wedding Night” was published in an unknown pulp confession magazine. January 13th 1978, Virginia sent a pitch letter to a literary agent with the writers workshop, Anita Diament. Three Days later Anita requested the entire manuscript. Virginia then, submitted her 98 page manuscript, “Flowers In the Attic.” Virginia sold the novel and was paid a $7,500 advance. “Petals On the Wind” was published the very next year and earned Virginia a $35,000 advance. “Petals On the Wind” remained on the bestseller list for 19 weeks, and “Flowers In the Attic” also returned to the list. Both of the novels sold 7 million copies within two years. In 1981 “If There Be Thorns” was released, earning Virginia a $75,000 advance. After this book, Virginia reached number 2 on many best-seller lists within the first two weeks of having the book published. huge success, already topping the sales of her other books. Two years later, Virginia published another book to the Dollanganger series, “Seeds Of Yesterday.” According to New York Times “Seeds Of Yesterday” was the best-selling fiction paperback novel of 1984. In 1985, “Heaven” The first book to the Casteel series, was released. Most fans say this was their favorite book by Virginia. In 1986 “Dark Angel” was published. Only three days after the publication of “Dark Angel” Virginia was number one on the best-seller lists. Also, in 1986, beating Stephen King, Virginia was named “Number One Best-Selling Author” of popular horror, and occult paperbacks by the American Booksellers Association. In 1986, while making “Flowers In the Attic” into a film, Virginia and her mother were on the set with the cast and crew.

huge success, already topping the sales of her other books. Two years later, Virginia published another book to the Dollanganger series, “Seeds Of Yesterday.” According to New York Times “Seeds Of Yesterday” was the best-selling fiction paperback novel of 1984. In 1985, “Heaven” The first book to the Casteel series, was released. Most fans say this was their favorite book by Virginia. In 1986 “Dark Angel” was published. Only three days after the publication of “Dark Angel” Virginia was number one on the best-seller lists. Also, in 1986, beating Stephen King, Virginia was named “Number One Best-Selling Author” of popular horror, and occult paperbacks by the American Booksellers Association. In 1986, while making “Flowers In the Attic” into a film, Virginia and her mother were on the set with the cast and crew.

of endeavor, outside advertising, and so diligent were the labors of the partners in building up a business that should credit their efforts that at one time they held privileges in thirty southern cities. Mr. Consolvo was president of this company, and after its organization had been completed and the burden of its management satisfactorily adjusted, he and Mr. Cheshire began the operation of the Norfolk Steam Laundry, the largest concern of its kind in this section of the state, Mr. Consolvo likewise holding the presidency of this enterprise.

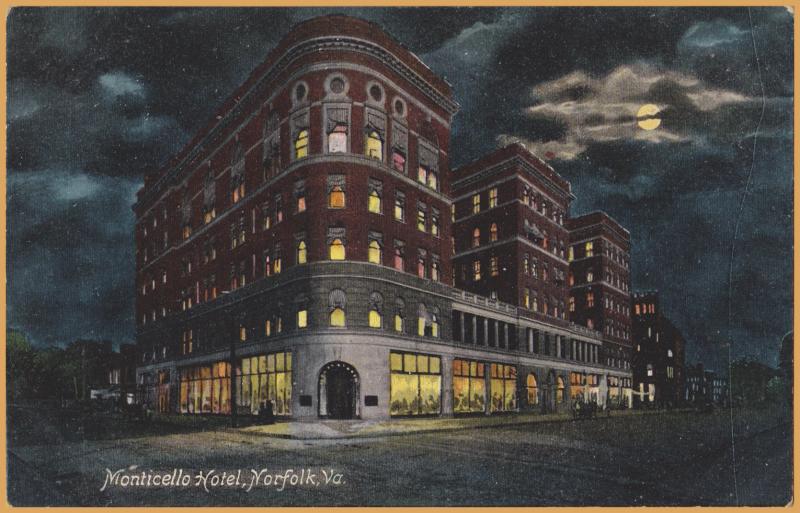

of endeavor, outside advertising, and so diligent were the labors of the partners in building up a business that should credit their efforts that at one time they held privileges in thirty southern cities. Mr. Consolvo was president of this company, and after its organization had been completed and the burden of its management satisfactorily adjusted, he and Mr. Cheshire began the operation of the Norfolk Steam Laundry, the largest concern of its kind in this section of the state, Mr. Consolvo likewise holding the presidency of this enterprise. Exposition, Mr. Consolvo secured the lease of the Monticello Hotel, of Norfolk, and also acquired the Pine Beach and Ocean View hotels. After the exposition he relinquished his personal management of the Pine Beach Hotel, although still controlling it and from 1903 to 1908 conducted the Monticello Hotel, of which Mr. Stokes was formerly the lessor. In the year 1911 the controlling company was formed, buying the property, of which Mr. Consolvo is president, and this company has made the Monticello Hotel one of the leading hotels of the South. It had a large capacity, containing three hundred and fifty rooms, and was magnificently appointed, many of the most elaborate social functions of the city was held in its luxurious ball room and banquet halls.

Exposition, Mr. Consolvo secured the lease of the Monticello Hotel, of Norfolk, and also acquired the Pine Beach and Ocean View hotels. After the exposition he relinquished his personal management of the Pine Beach Hotel, although still controlling it and from 1903 to 1908 conducted the Monticello Hotel, of which Mr. Stokes was formerly the lessor. In the year 1911 the controlling company was formed, buying the property, of which Mr. Consolvo is president, and this company has made the Monticello Hotel one of the leading hotels of the South. It had a large capacity, containing three hundred and fifty rooms, and was magnificently appointed, many of the most elaborate social functions of the city was held in its luxurious ball room and banquet halls. In 1906 he was appointed quartermaster of Virginia militia, ranking as captain of the Seventy-first Regiment of Infantry, this regiment afterward becoming the Fourth. In 1910 he was appointed by Governor Mann the first paymaster-general of Virginia militia with the rank of colonel. Additional honors from the chief executive of a state came to him in his appointment to the staff of the governor of Minnesota, a splendid courtesy which was largely in recognition of the cordial and hearty reception tendered the governor and his staff when they visited Norfolk en-route to Gettysburg. At this time Colonel Consolvo was the guest of honor at an elegant banquet in St. Paul, attended by the most prominent state officials and the most exclusive social circles of the city.

In 1906 he was appointed quartermaster of Virginia militia, ranking as captain of the Seventy-first Regiment of Infantry, this regiment afterward becoming the Fourth. In 1910 he was appointed by Governor Mann the first paymaster-general of Virginia militia with the rank of colonel. Additional honors from the chief executive of a state came to him in his appointment to the staff of the governor of Minnesota, a splendid courtesy which was largely in recognition of the cordial and hearty reception tendered the governor and his staff when they visited Norfolk en-route to Gettysburg. At this time Colonel Consolvo was the guest of honor at an elegant banquet in St. Paul, attended by the most prominent state officials and the most exclusive social circles of the city. and in each of these has displayed talent of worthy order. Although not consecutively, he had been for about fifteen years a member of the board of aldermen, always appointed to a place on the finance committee, his well-rewarded labors during his first term on this committee assuring him of such a place as frequently as he would consent to accept it. In this relation to the city’s administration he put into practice the same principles and methods that have won him prosperity in his private business, with inevitably satisfactory results. He was the president of the Jefferson Loan Society, and was a director in the Virginia National Bank and the Virginia Bank and Trust Company, he used to fraternize with the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks. He was a Roman Catholic in religion. His acquaintance and friendship was wide, and his genial and friendly nature attracted people and readily wins their confidence and liking.

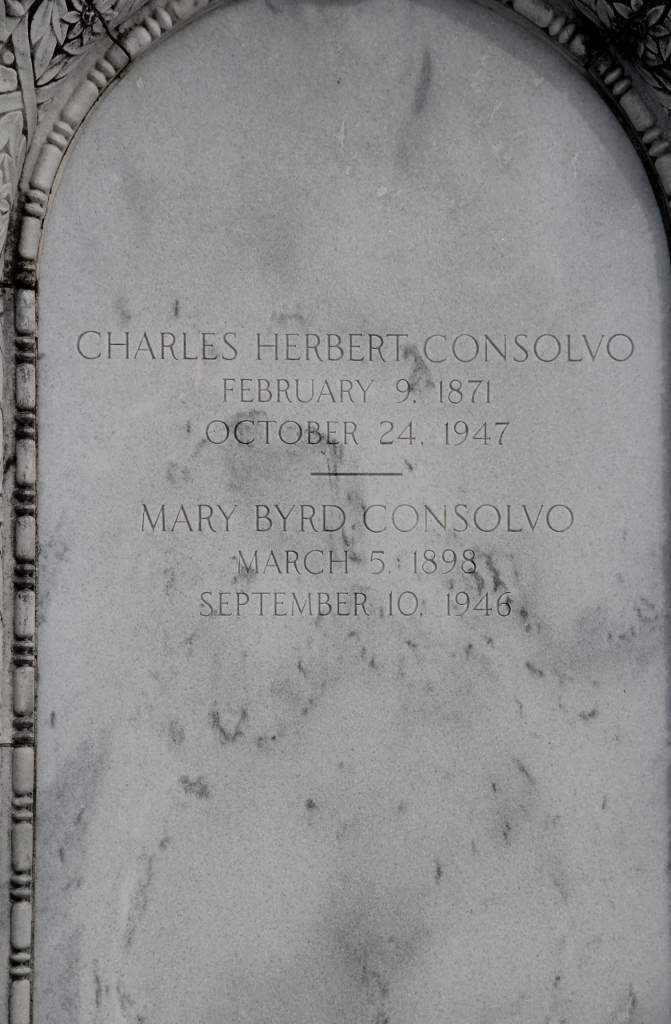

and in each of these has displayed talent of worthy order. Although not consecutively, he had been for about fifteen years a member of the board of aldermen, always appointed to a place on the finance committee, his well-rewarded labors during his first term on this committee assuring him of such a place as frequently as he would consent to accept it. In this relation to the city’s administration he put into practice the same principles and methods that have won him prosperity in his private business, with inevitably satisfactory results. He was the president of the Jefferson Loan Society, and was a director in the Virginia National Bank and the Virginia Bank and Trust Company, he used to fraternize with the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks. He was a Roman Catholic in religion. His acquaintance and friendship was wide, and his genial and friendly nature attracted people and readily wins their confidence and liking. Colonel Consolvo and his wife, Mary Byrd Consolvo, are buried together in a grande mausoleum in Forest Lawn Cemetery in Norfolk, Virginia. Charles died on Oct. 24, 1947 and is buried in the family mausoleum at Forest lawn right by the front gate and cemetery office. Colonel Charles H. Consolvo is a lineal descendant of {Prince Juan Consolvo, who assisted in expelling the Moors from Spain in 1860 A. D., a member of the royal house of Castile, the expulsion of these invaders checking the encroachments of Mohammedanism upon European territory. The later European records of the family were lost in the fire that destroyed the home of Francis Consolvo, of Princess Anne county, Virginia, and all that remains to the members thereof is the account of the generations of American residence, beginning with John Andrew Samuel Consolvo, who was born at Castile, Spain, in 1674.

Colonel Consolvo and his wife, Mary Byrd Consolvo, are buried together in a grande mausoleum in Forest Lawn Cemetery in Norfolk, Virginia. Charles died on Oct. 24, 1947 and is buried in the family mausoleum at Forest lawn right by the front gate and cemetery office. Colonel Charles H. Consolvo is a lineal descendant of {Prince Juan Consolvo, who assisted in expelling the Moors from Spain in 1860 A. D., a member of the royal house of Castile, the expulsion of these invaders checking the encroachments of Mohammedanism upon European territory. The later European records of the family were lost in the fire that destroyed the home of Francis Consolvo, of Princess Anne county, Virginia, and all that remains to the members thereof is the account of the generations of American residence, beginning with John Andrew Samuel Consolvo, who was born at Castile, Spain, in 1674.

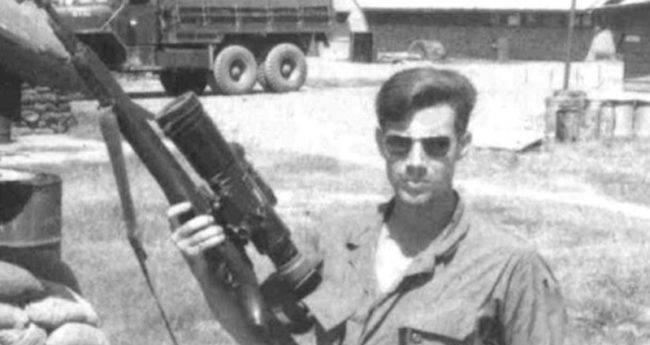

Before being deployed to South Vietnam, Hathcock met the love of his life, Jo Winstead. After receiving permission to marry her, the couple married on 10 November. In his spare time, Hathcock also began to participate in shooting championships, including the famous Wimbledon Cup (which he won in 1965). In 1966, however, Hathcock found himself in route to South Vietnam, as hostilities between North and South Vietnam had begun to deteriorate rapidly. Upon arrival, Hathcock was first deployed as a military policeman, but was quickly recruited by Captain Edward James Land into a sniper platoon. Land, upon discovering that Hathcock had won the Wimbledon Cup only a year prior, was greatly impressed with the young marksman’s abilities, and strongly felt that his talents were much better spent with sniping rather than police duty.

Before being deployed to South Vietnam, Hathcock met the love of his life, Jo Winstead. After receiving permission to marry her, the couple married on 10 November. In his spare time, Hathcock also began to participate in shooting championships, including the famous Wimbledon Cup (which he won in 1965). In 1966, however, Hathcock found himself in route to South Vietnam, as hostilities between North and South Vietnam had begun to deteriorate rapidly. Upon arrival, Hathcock was first deployed as a military policeman, but was quickly recruited by Captain Edward James Land into a sniper platoon. Land, upon discovering that Hathcock had won the Wimbledon Cup only a year prior, was greatly impressed with the young marksman’s abilities, and strongly felt that his talents were much better spent with sniping rather than police duty. was determined to change the role of snipers in warfare, as he believed that every platoon should possess at least one sharpshooter. Interested in this new concept, the Marine Corp allowed Captain Land to showcase and test the abilities of sniper units; providing Land and his new sniper platoon numerous opportunities to prove themselves along the way. In only a short amount of time, Hathcock’s shooting skills were immediately put to the test against both the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army. In total, it is estimated that Hathcock killed between 300 to 400 enemy personnel during his tours in Vietnam, although only 93 were confirmed kills, confirmed by an acting third-party officer.

was determined to change the role of snipers in warfare, as he believed that every platoon should possess at least one sharpshooter. Interested in this new concept, the Marine Corp allowed Captain Land to showcase and test the abilities of sniper units; providing Land and his new sniper platoon numerous opportunities to prove themselves along the way. In only a short amount of time, Hathcock’s shooting skills were immediately put to the test against both the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army. In total, it is estimated that Hathcock killed between 300 to 400 enemy personnel during his tours in Vietnam, although only 93 were confirmed kills, confirmed by an acting third-party officer.

One of the Hathcock’s most prized achievements was bringing down an enemy sniper with a shot right through his scope into his eye. Hathcock along with his spotter, John Roland Burke were sent on a mission in the nearby jungle to target the enemy sniper. The NVA sniper was called “the Cobra” and was feared for being very capable when it came to long range shooting. He had killed many Marines and was on a mission to eliminate Hathcock. Hathcock waited patiently in the jungle and as soon as he spotted a reflection of light from the Cobra’s scope, he aimed at him, putting the bullet straight into his eye. Later on, Hathcock analyzed the kill and concluded that shooting a sniper through his scope is only possible if both snipers are locked within each other’s sights. This meant Hathcock only had a few seconds to make his move, otherwise he would’ve died. Hathcock had his eyes on the trophy, i.e. the rifle and brought it back but it mysteriously went missing from the armory.

One of the Hathcock’s most prized achievements was bringing down an enemy sniper with a shot right through his scope into his eye. Hathcock along with his spotter, John Roland Burke were sent on a mission in the nearby jungle to target the enemy sniper. The NVA sniper was called “the Cobra” and was feared for being very capable when it came to long range shooting. He had killed many Marines and was on a mission to eliminate Hathcock. Hathcock waited patiently in the jungle and as soon as he spotted a reflection of light from the Cobra’s scope, he aimed at him, putting the bullet straight into his eye. Later on, Hathcock analyzed the kill and concluded that shooting a sniper through his scope is only possible if both snipers are locked within each other’s sights. This meant Hathcock only had a few seconds to make his move, otherwise he would’ve died. Hathcock had his eyes on the trophy, i.e. the rifle and brought it back but it mysteriously went missing from the armory. before any more damage could be inflicted by her. Then on one day, his spotter detected an NVA sniper team moving in at 700 yards. One of them took a break and squatted. Instantly, they knew it was the Apache. Hathcock calls it “the best shot he ever made”. The NVA patrol was aware of the dangers of peeing in the jungle and tried to stop her but she didn’t. It was too late for her anyways and Hathcock put two bullets in her, an extra one just to be safe!

before any more damage could be inflicted by her. Then on one day, his spotter detected an NVA sniper team moving in at 700 yards. One of them took a break and squatted. Instantly, they knew it was the Apache. Hathcock calls it “the best shot he ever made”. The NVA patrol was aware of the dangers of peeing in the jungle and tried to stop her but she didn’t. It was too late for her anyways and Hathcock put two bullets in her, an extra one just to be safe! All was well, when one day, Hathcock’s career came to an abrupt end. In September 1969, north of LZ Baldy, just along Route 1, Hathcock’s amtrack was blown up by an anti-tank mine. Fire broke out and Hathcock took the charge of taking out 7 injured marines. He, himself was severely burned and it was clear that it would take a long time before he was on his feet again. Hathcock got a Purple Heart for his conduct.

All was well, when one day, Hathcock’s career came to an abrupt end. In September 1969, north of LZ Baldy, just along Route 1, Hathcock’s amtrack was blown up by an anti-tank mine. Fire broke out and Hathcock took the charge of taking out 7 injured marines. He, himself was severely burned and it was clear that it would take a long time before he was on his feet again. Hathcock got a Purple Heart for his conduct.

After two years in West Computing, Jackson was offered a computing position to work with engineer Kazimierz Czarnecki. In addition to her computing tasks, Czarnecki offered her hands-on experience conducting experiments in the facility and encouraged her to enter a training program that would allow her to earn a promotion from mathematician to engineer. Trainees had to take graduate-level math and physics in after-work courses. Because the classes were held at then-segregated Hampton High School, she petitioned and received special permission from the City of Hampton to join her white peers in the classroom. Jackson completed the courses, earned the promotion, and in 1958 became NASA’s first African American female engineer. She specialized in the incredibly complex field of boundary layer effects on aerospace vehicle configurations at supersonic speeds. That same year, she co-authored her first report, “Effects of Nose Angle and Mach Number on Transition on Cones at Supersonic Speeds.” By 1975, she had authored or co-authored a total of 12 NACA and NASA technical publications.

After two years in West Computing, Jackson was offered a computing position to work with engineer Kazimierz Czarnecki. In addition to her computing tasks, Czarnecki offered her hands-on experience conducting experiments in the facility and encouraged her to enter a training program that would allow her to earn a promotion from mathematician to engineer. Trainees had to take graduate-level math and physics in after-work courses. Because the classes were held at then-segregated Hampton High School, she petitioned and received special permission from the City of Hampton to join her white peers in the classroom. Jackson completed the courses, earned the promotion, and in 1958 became NASA’s first African American female engineer. She specialized in the incredibly complex field of boundary layer effects on aerospace vehicle configurations at supersonic speeds. That same year, she co-authored her first report, “Effects of Nose Angle and Mach Number on Transition on Cones at Supersonic Speeds.” By 1975, she had authored or co-authored a total of 12 NACA and NASA technical publications. Among her many honors were an Apollo Group Achievement Award, and being named Langley’s Volunteer of the Year in 1976. She served as the Chairperson for one of the Center’s annual United Way campaigns, was a Girl Scout troop leader for more than three decades, and was a member of the National Technical Association (the oldest African American technical organization in the United States).

Among her many honors were an Apollo Group Achievement Award, and being named Langley’s Volunteer of the Year in 1976. She served as the Chairperson for one of the Center’s annual United Way campaigns, was a Girl Scout troop leader for more than three decades, and was a member of the National Technical Association (the oldest African American technical organization in the United States). Mary Jackson passed away in Hampton on February 11, 2005, at the age of 83. She was preceded in death by her husband, Levi Jackson Sr, and was survived by her son, Levi Jackson Jr, her daughter, Carolyn Marie Lewis and her granddaughter, Wanda D.Jackson.

Mary Jackson passed away in Hampton on February 11, 2005, at the age of 83. She was preceded in death by her husband, Levi Jackson Sr, and was survived by her son, Levi Jackson Jr, her daughter, Carolyn Marie Lewis and her granddaughter, Wanda D.Jackson.

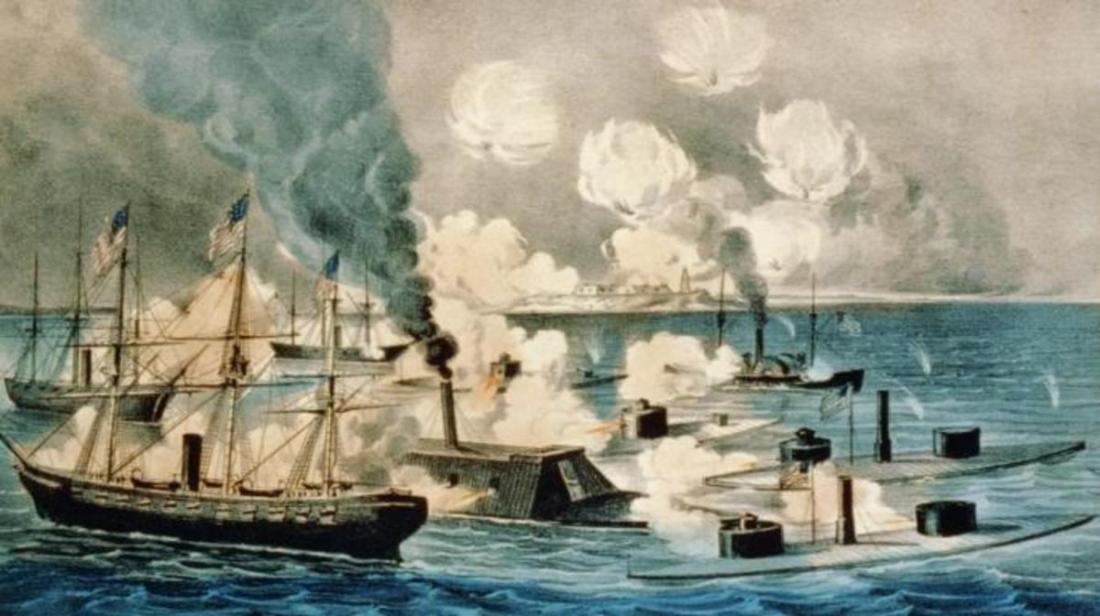

that city when he joined the Navy in 1850. He served during the Civil War as a Master-at-Arms on the USS Richmond during the Battle of Mobile Bay. The Battle of Mobile Bay was on August 5, 1864 was an engagement of the American Civil War in which a Union fleet commanded by Rear Admiral David G. Farragut, assisted by a contingent of soldiers, attacked a smaller Confederate fleet led by Admiral Franklin Buchanan and three forts that guarded the entrance to Mobile Bay. A paraphrase of his order, “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!” became famous”.

that city when he joined the Navy in 1850. He served during the Civil War as a Master-at-Arms on the USS Richmond during the Battle of Mobile Bay. The Battle of Mobile Bay was on August 5, 1864 was an engagement of the American Civil War in which a Union fleet commanded by Rear Admiral David G. Farragut, assisted by a contingent of soldiers, attacked a smaller Confederate fleet led by Admiral Franklin Buchanan and three forts that guarded the entrance to Mobile Bay. A paraphrase of his order, “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!” became famous”. The battle was marked by Farragut’s seemingly rash but successful run through a minefield that had just claimed one of his ironclad monitors, enabling his fleet to get beyond the range of the shore-based guns. This was followed by a reduction of the Confederate fleet to a single vessel, ironclad CSS Tennessee. Tennessee did not then retire, but engaged the entire Northern fleet. Tennessee’s armor enabled her to inflict more injury than she received, but she could not overcome the imbalance in numbers. She was eventually reduced to a motionless hulk and surrendered, ending the battle. With no Navy to support them, the three forts also surrendered within days. Complete control of lower Mobile Bay thus passed to the Union forces.

The battle was marked by Farragut’s seemingly rash but successful run through a minefield that had just claimed one of his ironclad monitors, enabling his fleet to get beyond the range of the shore-based guns. This was followed by a reduction of the Confederate fleet to a single vessel, ironclad CSS Tennessee. Tennessee did not then retire, but engaged the entire Northern fleet. Tennessee’s armor enabled her to inflict more injury than she received, but she could not overcome the imbalance in numbers. She was eventually reduced to a motionless hulk and surrendered, ending the battle. With no Navy to support them, the three forts also surrendered within days. Complete control of lower Mobile Bay thus passed to the Union forces. rammed by the Tennessee in Mobile Bay, 5 August 1864. Despite damage to his ship and the loss of several men on board as enemy fire raked her decks, Carr performed his duties with skill and courage throughout the prolonged battle which resulted in the surrender of the Tennessee and in the successful attacks carried out on Fort Morgan. For this action, he was awarded the Medal of Honor four months later, on December 31, 1864. William Died on May 4, 1884 buried in Elmwood Cemetery at Third Avenue East Lot 39.

rammed by the Tennessee in Mobile Bay, 5 August 1864. Despite damage to his ship and the loss of several men on board as enemy fire raked her decks, Carr performed his duties with skill and courage throughout the prolonged battle which resulted in the surrender of the Tennessee and in the successful attacks carried out on Fort Morgan. For this action, he was awarded the Medal of Honor four months later, on December 31, 1864. William Died on May 4, 1884 buried in Elmwood Cemetery at Third Avenue East Lot 39. Hendrick Sharp was a Union Navy sailor in the American Civil War and a recipient of the U.S. military’s highest decoration, the Medal of Honor, for his actions at the Battle of Mobile Bay. Born in 1815 in Spain, Sharp immigrated to the United States and was living in New York when he joined the U.S. Navy. He served in the Civil War as a seaman and gun captain on the USS Richmond. During the Battle of Mobile Bayon August 5, 1864, he “fought his gun with skill and courage” despite heavy fire. For this action, he was awarded the Medal of Honor four months later, on December 31, 1864.

Hendrick Sharp was a Union Navy sailor in the American Civil War and a recipient of the U.S. military’s highest decoration, the Medal of Honor, for his actions at the Battle of Mobile Bay. Born in 1815 in Spain, Sharp immigrated to the United States and was living in New York when he joined the U.S. Navy. He served in the Civil War as a seaman and gun captain on the USS Richmond. During the Battle of Mobile Bayon August 5, 1864, he “fought his gun with skill and courage” despite heavy fire. For this action, he was awarded the Medal of Honor four months later, on December 31, 1864. Richmond during action against rebel forts and gunboats and with the ram

Richmond during action against rebel forts and gunboats and with the ram

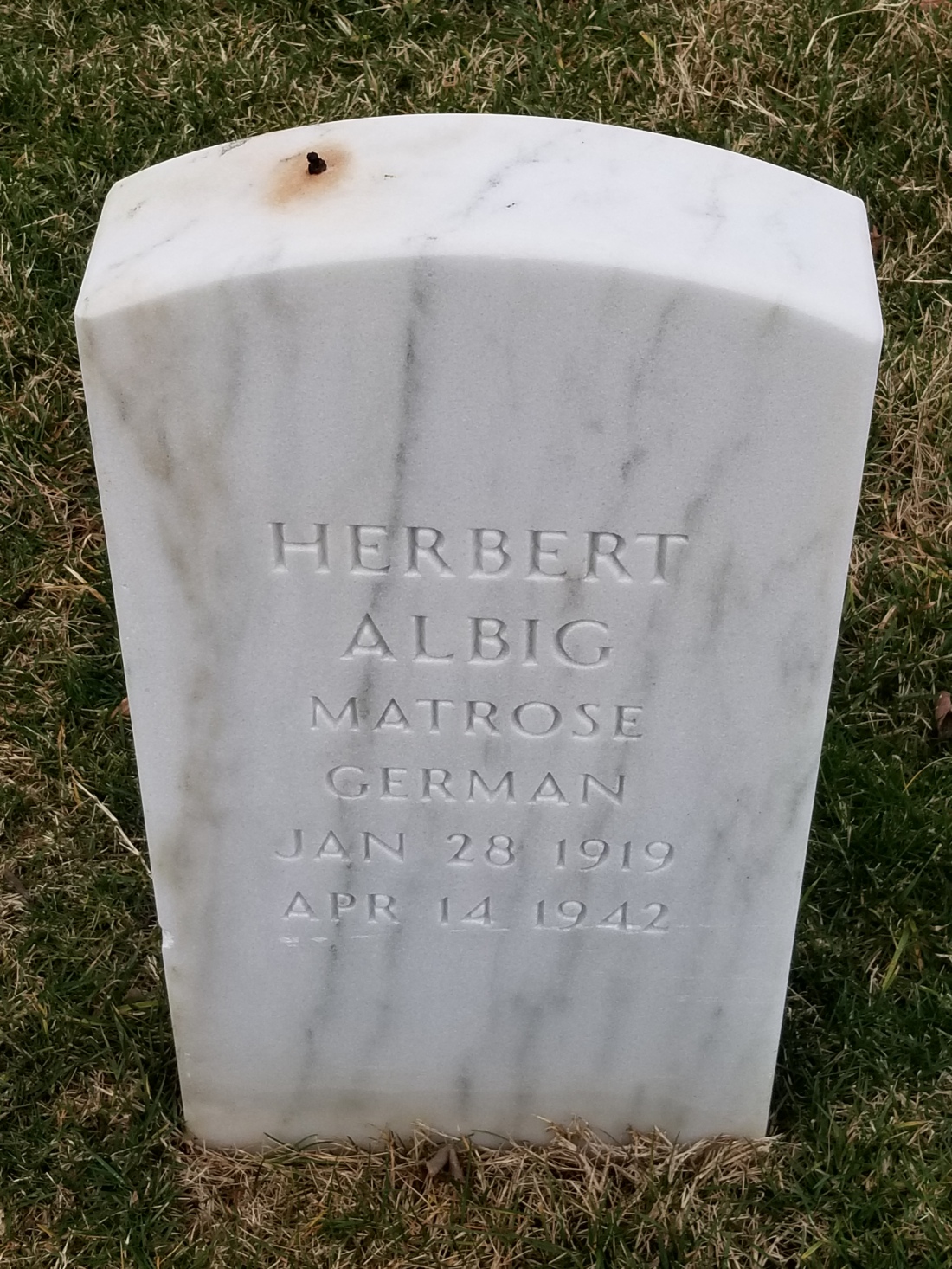

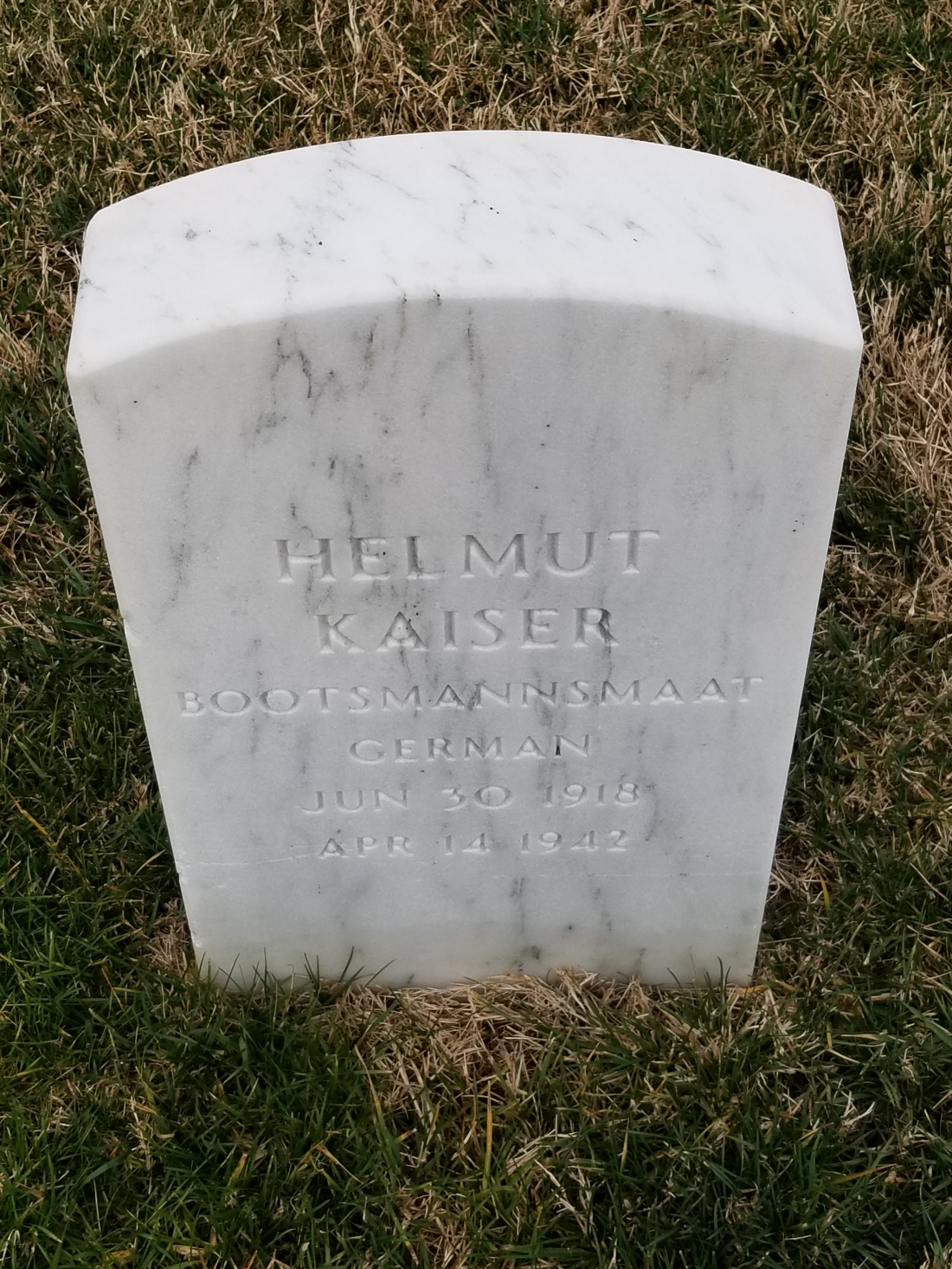

their country, a bugler sounded taps as a small squad of men in dress uniform fired a three-volley salute over the freshly dug graves. Officers of the United States Army and Navy stood silently at attention as two navy chaplains officiated: Lieutenant Wilbur F. X. Wheeler read the Catholic requiem and Lieutenant (junior grade) Rainus A. Lundquist performed Protestant rites. On 15 April 1942 when the dead were laid to rest in Hampton National Cemetery, they joined nearly twenty thousand others interred there since 1862. Like the veterans before them, each was buried along a neat, straight row with a white marble headstone later added to mark the place.

their country, a bugler sounded taps as a small squad of men in dress uniform fired a three-volley salute over the freshly dug graves. Officers of the United States Army and Navy stood silently at attention as two navy chaplains officiated: Lieutenant Wilbur F. X. Wheeler read the Catholic requiem and Lieutenant (junior grade) Rainus A. Lundquist performed Protestant rites. On 15 April 1942 when the dead were laid to rest in Hampton National Cemetery, they joined nearly twenty thousand others interred there since 1862. Like the veterans before them, each was buried along a neat, straight row with a white marble headstone later added to mark the place. There were no American flags draping the caskets and the names stenciled on each box were unfamiliar: Weidmann, Heiter, Schoen, and Degenkolb. They were German names. The service was for 29 of the 44 officers and crewmen of the German Submarine U-85. The 15 other bodies were never recovered after the destroyer USS Roper attacked and sank the submarine off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, in the early hours of 14 April. It was the war’s first German Submarine destroyed by an American vessel in home waters, and the first time a foreign enemy had been buried on American soil since the War of 1812.

There were no American flags draping the caskets and the names stenciled on each box were unfamiliar: Weidmann, Heiter, Schoen, and Degenkolb. They were German names. The service was for 29 of the 44 officers and crewmen of the German Submarine U-85. The 15 other bodies were never recovered after the destroyer USS Roper attacked and sank the submarine off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, in the early hours of 14 April. It was the war’s first German Submarine destroyed by an American vessel in home waters, and the first time a foreign enemy had been buried on American soil since the War of 1812. Lorient, France, en route to it patrol station off the Virginia coast. The U-85 was one of the 691 Type VII U-boats constructed during the war, numbering more than any other series of warship ever built. The U-85 itself was built in Lubeck, Germany, in early 1941 with a hill slightly modified for Atlantic service, making it one of the Type VII-B series, of which there were only 24. For both the boat and its commander, Kapitanleutant Eberhard Greger, it was the 4th war patrol, but his first in American waters. The U-85 had already been credited with sinking British steamers Thistleglen and Empire Fusilier and had survived two destroyer and four air attacks.

Lorient, France, en route to it patrol station off the Virginia coast. The U-85 was one of the 691 Type VII U-boats constructed during the war, numbering more than any other series of warship ever built. The U-85 itself was built in Lubeck, Germany, in early 1941 with a hill slightly modified for Atlantic service, making it one of the Type VII-B series, of which there were only 24. For both the boat and its commander, Kapitanleutant Eberhard Greger, it was the 4th war patrol, but his first in American waters. The U-85 had already been credited with sinking British steamers Thistleglen and Empire Fusilier and had survived two destroyer and four air attacks. The U-85 carried 14 torpedoes. With a range of almost five miles, each could be launched from either stern or forward torpedo tubes, and carried 800 pounds of high explosive. In addition, mounted on the submarines deck was an 88-mm cannon for surface attacks and on the conning tower a 20- mm machine gun to protect the U-boat from enemy aircraft. For defense from depth charges, the U-boat’s hull was designed to withstand pressures at depths of several hundred feet.

The U-85 carried 14 torpedoes. With a range of almost five miles, each could be launched from either stern or forward torpedo tubes, and carried 800 pounds of high explosive. In addition, mounted on the submarines deck was an 88-mm cannon for surface attacks and on the conning tower a 20- mm machine gun to protect the U-boat from enemy aircraft. For defense from depth charges, the U-boat’s hull was designed to withstand pressures at depths of several hundred feet. By the night of 13 April, the submarine was prowling off the cape, hungry and overdue for another kill. Cruising on the surface, the U-85 headed south at 16 knots. There in the dark the U-85 was traveling on the surface and was being followed by the USS Roper (DD-147). The captain and four young lookouts, unknowing, stared ahead from the darkened conning tower looking for their next target, just a few feet above the water. Finally only a thousand yards away, the Roper was finally spotted by the U-boats spotters. U-85 changed position and did not submerge but continued to gain good attack position to attack the Roper.

By the night of 13 April, the submarine was prowling off the cape, hungry and overdue for another kill. Cruising on the surface, the U-85 headed south at 16 knots. There in the dark the U-85 was traveling on the surface and was being followed by the USS Roper (DD-147). The captain and four young lookouts, unknowing, stared ahead from the darkened conning tower looking for their next target, just a few feet above the water. Finally only a thousand yards away, the Roper was finally spotted by the U-boats spotters. U-85 changed position and did not submerge but continued to gain good attack position to attack the Roper. found a U-boat. Suddenly, startled crewmen screamed in alarm and pointed into the water alongside their ship. A glistening trail of bubbles – a torpedo, passed by only a few feet from the destroyer’s side. Roper continued to chase U-85 and ordered the ships search lights to be turned on within 300 hundred yards of the U-boat. Immediately they say the U-boat floating on the surface. Every machine gun on the Roper opened fired. Killing all the u-boat men that were standing on the surface of the U-boat.

found a U-boat. Suddenly, startled crewmen screamed in alarm and pointed into the water alongside their ship. A glistening trail of bubbles – a torpedo, passed by only a few feet from the destroyer’s side. Roper continued to chase U-85 and ordered the ships search lights to be turned on within 300 hundred yards of the U-boat. Immediately they say the U-boat floating on the surface. Every machine gun on the Roper opened fired. Killing all the u-boat men that were standing on the surface of the U-boat. U-85 was ordered to crash dive. In thirty seconds the ship was surrounded by water. Now directly parallel to the submarine, the Roper’s captain saw that the U-boat was going under. The roper fired her three inch guns, all shots went wide. Roper then fired her torpedoes at the submerging U-boat, but at three hundred yards they were too close. Then the number five gun fired and hit U-85 and explosion could be heard from the sub. The conning tower had a gaping hole and smoke was seen coming from it. U-85 was finished. Icy water began to pour into the submarine. The Germans began to abandon ship, many waving their arms to the Roper to save them. Roper fearing another sub might be close by to the U-85 ordered his men to drop depth charges in the area where the German Sailors

U-85 was ordered to crash dive. In thirty seconds the ship was surrounded by water. Now directly parallel to the submarine, the Roper’s captain saw that the U-boat was going under. The roper fired her three inch guns, all shots went wide. Roper then fired her torpedoes at the submerging U-boat, but at three hundred yards they were too close. Then the number five gun fired and hit U-85 and explosion could be heard from the sub. The conning tower had a gaping hole and smoke was seen coming from it. U-85 was finished. Icy water began to pour into the submarine. The Germans began to abandon ship, many waving their arms to the Roper to save them. Roper fearing another sub might be close by to the U-85 ordered his men to drop depth charges in the area where the German Sailors were screaming to be rescued. On each pass the destroyer dropped 1,200 pounds of TNT into the ocean amid the helpless German sailors. The bodies of 31 floated in the water near where the U-boat had gone down, all died from the depth charges from the Roper. No Germans were found alive, and no other U-boat were ever found. In all, the Roper recovered 29 bodies. The bodies of two men were in such poor condition from the depth charges that they were allowed to sink back into the ocean. Kapitanleutnant Eberhard Greger’s body was never found.

were screaming to be rescued. On each pass the destroyer dropped 1,200 pounds of TNT into the ocean amid the helpless German sailors. The bodies of 31 floated in the water near where the U-boat had gone down, all died from the depth charges from the Roper. No Germans were found alive, and no other U-boat were ever found. In all, the Roper recovered 29 bodies. The bodies of two men were in such poor condition from the depth charges that they were allowed to sink back into the ocean. Kapitanleutnant Eberhard Greger’s body was never found.

Richard Thomas Shea, Jr. was a soldier in the United States Army in the Korean War. He was listed as missing in action on July 8, 1953 during the Second Battle of Pork Chop Hill, and was later declared killed in action. Lt. Shea received the Medal of Honor posthumously. In 1987, Shea was inducted into the Virginia Sports Hall of Fame. A native of Portsmouth, Virginia, Shea graduated from Churchland High School. He first studied in uniform at Virginia Polytechnic Institute at the height of World War II, but left early to join the US Army in 1944. He served in the US Constabulary in post-war Europe, rising to the rank of staff Sergeant, before he entered West Point in 1948.

Richard Thomas Shea, Jr. was a soldier in the United States Army in the Korean War. He was listed as missing in action on July 8, 1953 during the Second Battle of Pork Chop Hill, and was later declared killed in action. Lt. Shea received the Medal of Honor posthumously. In 1987, Shea was inducted into the Virginia Sports Hall of Fame. A native of Portsmouth, Virginia, Shea graduated from Churchland High School. He first studied in uniform at Virginia Polytechnic Institute at the height of World War II, but left early to join the US Army in 1944. He served in the US Constabulary in post-war Europe, rising to the rank of staff Sergeant, before he entered West Point in 1948. attend West Point. He ran his first competitive race at VPI. One of the West Point Black Knights’ most celebrated distance runners, Dick Shea captured Heptagonal and IC4A individual cross country titles in three successive years 1949 to 1951, helping Army to three straight team titles during that time. The top performer on Army’s dominant cross country team, Shea led the Black Knights to a 19-2 record during his West Point career, a mark that included three straight “shutouts” of arch-rival Navy. He set seven Academy records in indoor and

attend West Point. He ran his first competitive race at VPI. One of the West Point Black Knights’ most celebrated distance runners, Dick Shea captured Heptagonal and IC4A individual cross country titles in three successive years 1949 to 1951, helping Army to three straight team titles during that time. The top performer on Army’s dominant cross country team, Shea led the Black Knights to a 19-2 record during his West Point career, a mark that included three straight “shutouts” of arch-rival Navy. He set seven Academy records in indoor and  outdoor track and field and established a meet record in the 2 miles run at the prestigious Penn Relays in 1951. Shea repeated as the two-mile champ at both the Penn Relays and Heptagonal Championships in 1951 and 1952. His standards in the indoor 1 mile run (4:10) and 2 miles run (9:05.8) remained on Army’s record books for more than a decade. Since 1952, only eight Army runners have achieved a better time in the mile, either indoors or outdoors. Today, Army’s outdoor track and field complex bears his name. Turning down the opportunity to attend the Olympic Games, after graduating in 1952, he joined his classmates in the Korean War.

outdoor track and field and established a meet record in the 2 miles run at the prestigious Penn Relays in 1951. Shea repeated as the two-mile champ at both the Penn Relays and Heptagonal Championships in 1951 and 1952. His standards in the indoor 1 mile run (4:10) and 2 miles run (9:05.8) remained on Army’s record books for more than a decade. Since 1952, only eight Army runners have achieved a better time in the mile, either indoors or outdoors. Today, Army’s outdoor track and field complex bears his name. Turning down the opportunity to attend the Olympic Games, after graduating in 1952, he joined his classmates in the Korean War. first lieutenant and acting company commander at Pork Chop Hill, Sokkogae, Korea during the Korean War. Fighting outnumbered, he voluntarily proceeded to the area most threatened, organizing and leading a counterattack. In the ensuing bitter fighting, he killed two of the enemy with his trench knife. In over 18 hours of heavy fighting, he moved among the defenders of Pork Chop Hill organizing a successful defense. Leading a counterattack, he killed three enemy soldiers single-handedly. Wounded he refused evacuation. He was last seen alive fighting hand-to-hand while leading another desperate counterattack.

first lieutenant and acting company commander at Pork Chop Hill, Sokkogae, Korea during the Korean War. Fighting outnumbered, he voluntarily proceeded to the area most threatened, organizing and leading a counterattack. In the ensuing bitter fighting, he killed two of the enemy with his trench knife. In over 18 hours of heavy fighting, he moved among the defenders of Pork Chop Hill organizing a successful defense. Leading a counterattack, he killed three enemy soldiers single-handedly. Wounded he refused evacuation. He was last seen alive fighting hand-to-hand while leading another desperate counterattack.

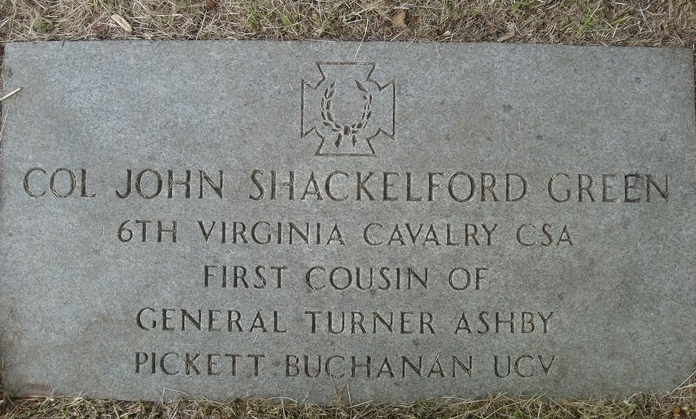

John “Shac” Shackleford Green was born on June 9, 1817, in Rappahannock County, Virginia and became a farmer. In response to the April 14, 1861, surrender at Fort Sumter, President Lincoln raised the call for 75,000 volunteers to put down the southern rebellion. In turn, Green enlisted in the Confederacy on April 22, 1861. After the formation of the 6th Virginia Calvary, he became a Captain in Company B.

John “Shac” Shackleford Green was born on June 9, 1817, in Rappahannock County, Virginia and became a farmer. In response to the April 14, 1861, surrender at Fort Sumter, President Lincoln raised the call for 75,000 volunteers to put down the southern rebellion. In turn, Green enlisted in the Confederacy on April 22, 1861. After the formation of the 6th Virginia Calvary, he became a Captain in Company B. acquitted by court-martial of disobedience of orders and breach of arrest on September 17, 1863. Green resigned on April 23, 1864 for the good of the service. On this General Jeb Stuart wrote that Green “deserves credit for his patriotism. The service will be benefited beyond a doubt by its acceptance.” His resignation was recorded as of May 19, 1864.

acquitted by court-martial of disobedience of orders and breach of arrest on September 17, 1863. Green resigned on April 23, 1864 for the good of the service. On this General Jeb Stuart wrote that Green “deserves credit for his patriotism. The service will be benefited beyond a doubt by its acceptance.” His resignation was recorded as of May 19, 1864.